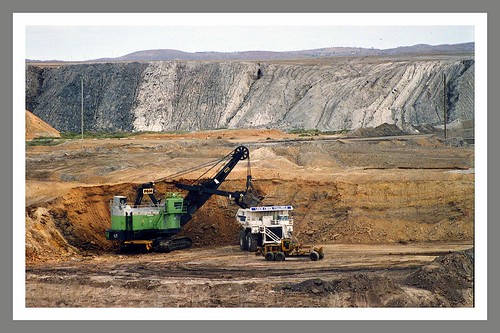

Riding On The Back Of A Coal Truck

Posted by Big Gav on April 23, 2008 - 8:18am in The Oil Drum: Australia/New Zealand

I was complaining about the "Australian disease" in my post about coal to liquids last week, as it became clear just how much King Coal is coming to dominate the local economy.

Ross Gittens can see the sunny side of this though in today's Sydney Morning Herald, as he idly contemplates the de-industrialisation of the economy and the transformation of the nation into a giant quarry in "Everything's coming up roses", in which he predicts that we'll be "riding on the back of a coal truck" for the next few decades.

Global warming apparently isn't a problem in his eyes - or at least not one that people will bother to try and mitigate by burning less coal.

Powerful forces are at work that most of us are only dimly aware of. They will persist despite any economic slowdown and change the face of our economy.

The re-emergence of China and India as major economic powers is changing the structure of the world economy. These are the two most populous countries - accounting for almost 40 per cent of the globe's population - and when they start growing strongly and treading the well-trodden path of economic development they make a big difference.

Until now, the world economy has been growing unusually strongly. But get this: last year the United States, Europe and Japan accounted for only about 20 per cent of the growth in gross world product, whereas China and India - with help from Russia and Brazil - accounted for more than 40 per cent of that growth.

China is doing more than just churning out loads of cheap exports. It's busy turning a backward, rural economy into a modern industrial economy that will eventually yield its citizens a standard of living in the same ballpark as ours.

It's in the process of catching up with the developed world, achieving in the space of, say, 50 years what took the West 200 years. That's possible because of infusions of developed-country capital and, more importantly, technology.

This rapid development involves humungous expenditure on all the things we take for granted: roads, railways, bridges, power stations, housing and much else. This, in turn, requires huge quantities of energy and raw materials.

Among many other resources, China is consuming well over a third of the world's annual production of coal and iron ore. But China has a relatively low endowment of natural resources per person.

This is where we come in, of course. Australia accounts for about half the world's annual production of coking coal (for making steel) and about a fifth of the world's production of steaming coal (for generating electricity) and iron ore.

Rural and mineral commodities have always dominated our exports. The prices the world pays for those commodities vary greatly from year to year according to the vagaries of world demand and supply. In consequence, we've enjoyed "commodity booms" - periods of high world commodity prices - roughly every 20 or 30 years.

The present resources boom is probably the biggest we've ever experienced. The contract prices we receive for coal are expected to almost triple this year, with prices for iron ore leaping by a paltry 65 per cent.

Here's the point: unlike every other, fleeting commodity boom we've experienced, this one is likely to be permanent. Why? Because it's produced not by a temporary surge in the developed countries' demand for commodities, but by the industrialisation of the Chinese and Indian economies, a process that's likely to last for several decades.

Coal and iron ore prices will eventually fall back from their present sky-high levels, of course. But not until we and our competitor countries have greatly increased our production of those commodities. And even when they've fallen, prices are likely to remain much higher than they were.

See what this means? Throughout most of last century we watched the relative prices of our primary commodity exports steadily decline. The stuff we had to sell the developed world constituted an ever-diminishing share of its needs. We were backing a loser.

But with the development of China, India and other emerging economies, commodity-exporting countries like us are back on top. The stuff we've got to sell is now in great and continuing demand. We've returned to riding on the back of a coal truck.

This is great news. As a nation we're now a lot richer than we thought we were and can enjoy a significantly higher standard of living.

(The news will, however, discomfort people who're convincing themselves it's a sin to sell coal and those who imagine global warming will somehow halt the poor countries' economic development. Remember that most of what we're selling the Chinese goes to make steel, not electricity.)

But just as the re-emergence of China and India is changing the structure of the world economy, so our part in that re-emergence will change the structure of our economy - in ways many people won't like.

This restoration of Australia's comparative advantage in mining will require us to shift resources out of other industries and into mining. Our manufacturers are likely to be first in the firing line, although inbound tourism will also take a hit. Our soaring dollar will stay high as part of the pressure on these industries to contract.

For readers overseas who don't understand the coal truck reference, traditionally (back in the day when the country was just a giant sheep farm that supplied raw materials for British textile mills) the Australian economy was described as "riding on the sheep's back".

Cross posted from Peak Energy

I agree with Bob Brown that one day we will look upon coal the way we now regard asbestos, in terms of 'what were we thinking?'. I think of it as an own goal whereby we get jobs and export revenue in return for drought, misery, high food prices and Nauru-like temporary financial dependence.

Granted Australian coal exports are minor in terms of global demand but on principle we could decline to peddle an unhealthy product. I suggest that exports be subject to the same reducing cap as domestic carbon in the long awaited trading scheme. If the ETS finally arrives in 2012 all of the years 2008-2011 will have been available to get it right. However I'm near certain it will be a dogs breakfast of giveaways. Even if it were stringent it seems odd that while domestic coal and gas users progressively cut back somehow when foreigners burn more of our fossil fuel that's a good thing.

A saving grace may be price increases. 50% a year for 4 years is a 5-fold increase. This factor, along with food chaos and lack of liquid fuel could mean the coal burning business-as-usual economy will disintegrate anyway. So now is the time to transition to low carbon and take some pain now rather than more pain later.

Personal note: when I moved to Tasmania in 2004 the state grid was 0% coal powered. Now it is 13% thanks to the Basslink HVDC cable. April is shaping up to be the driest ever recorded and it it looks like I'll have to beef up my solar garden pumping system from surface water to groundwater.

This is something that enrages some of my friends in the energy industry - solving one problem without reference to the other problem. Ultimately shareholders decide what a publicly floated company does. The shareholders can act out of idealism, or they can act because the price of carbon is hitting the bottom line...but somehow they need to be persuaded to act.

Ideally, it would be tackled both ways.

David C.

Australia has made a deal with the devil and the devil is coal. Its like we’ve harvested a bumper crop of opium poppies and the economists are applauding the high price of herion and telling us how much richer we’ll all be (ugh!). It may be a radical view now, but I am utterly convinced this is how we will view this dark period in Australia’s history in … oh, around 2020.

P.S. Its Gittins with an 'i'

Hmmm - I could have sworn it was Gittens - my tendency to quickly scan news items these days is doing terrible things to my spelling...